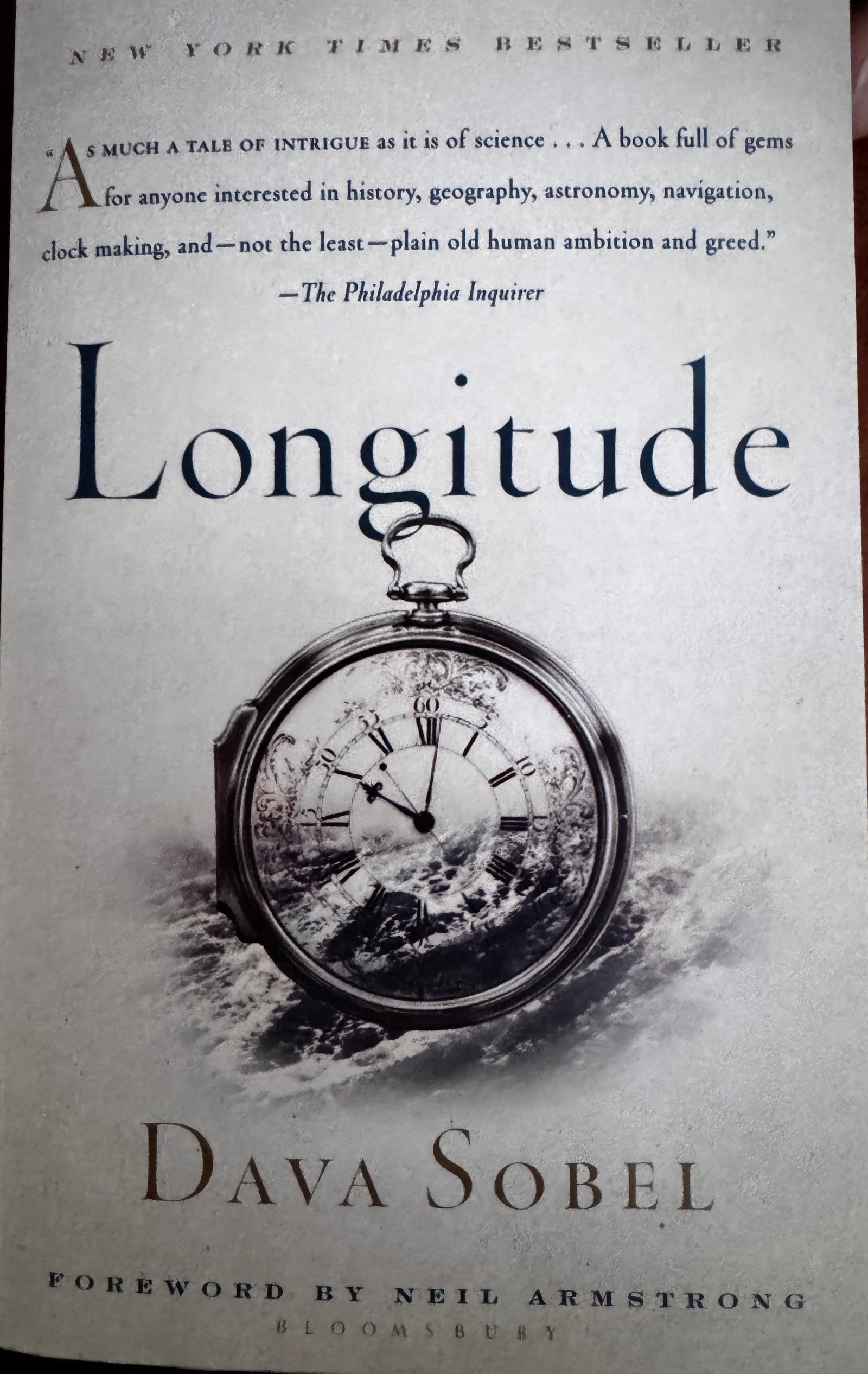

In 1675 King Charles II commissioned Sir Christopher Wren to build an observatory in Greenwich, England to “improve marine navigation and find the so-much desired longitude at sea for perfecting the art of navigation," this according to an excellent book by Dava Sobel, Longitude, which dives deep into the whole business of longitude and time.

Not coincidentally, Wren's observatory is the location of the Prime Meridian. “An imaginary plane passing through the observatory and through the Earth’s North and South Poles will cleave the Earth precisely into eastern and western hemispheres” hence becoming the base for Greenwich Mean Time. Perhaps an excellent modern day trivia question; where does each day, year and century actually begin? Answer, anywhere along the Prime Meridian!

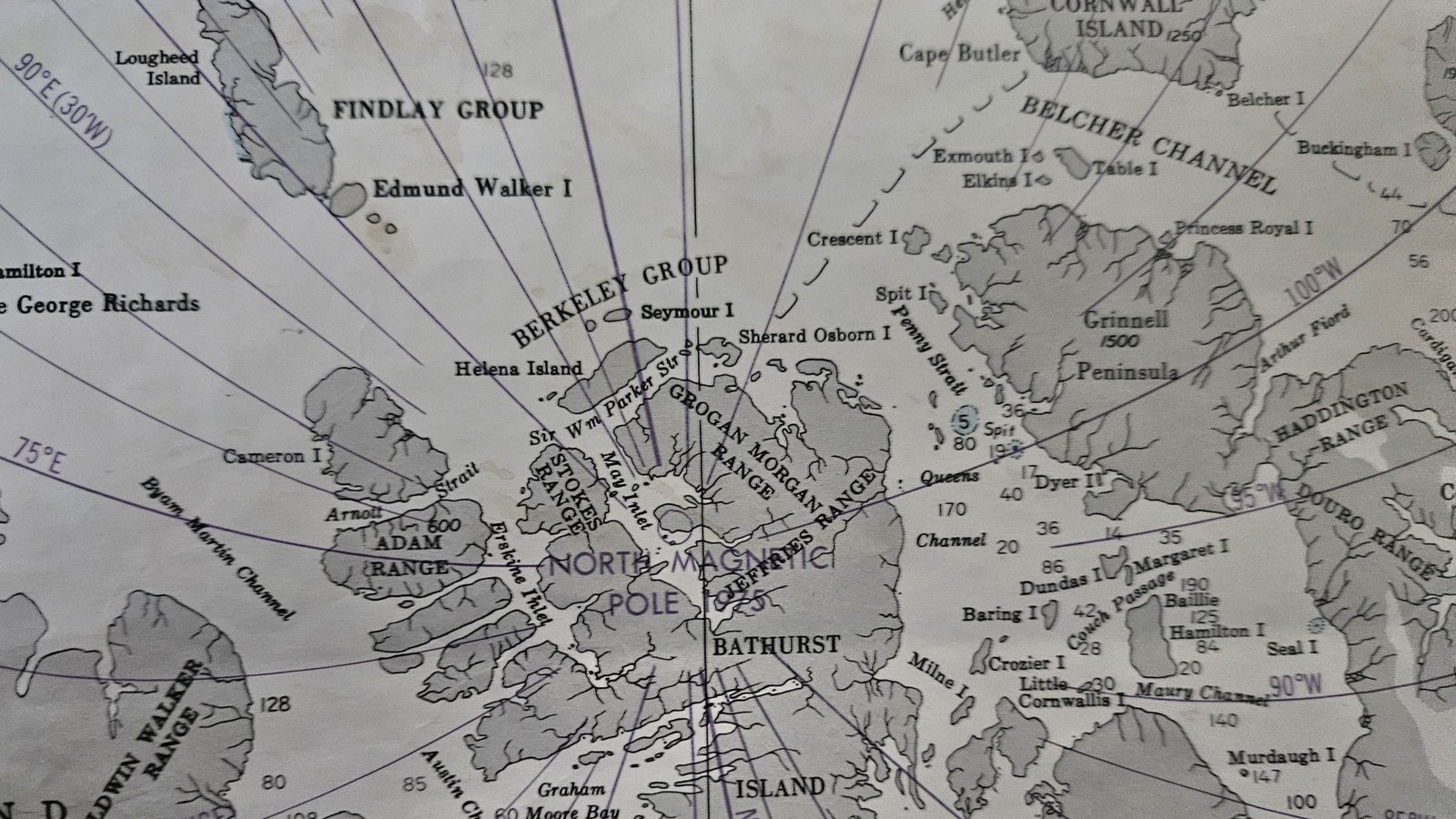

It is hard for us to imagine the challenges of early arctic exploration. At this moment we are completely surrounded by examples of the difficulties and tragedies experienced during the periods of discovery in these latitudes. Early ship Captains understood the meaning of latitude and could measure it in the Northern Hemisphere by measuring the elevation of the North Star above the horizon. The same holds true in the Southern Hemisphere using stars in the Southern Cross (with some additional correction). However, latitude dancing alone might not get you home.

Meridians are not very helpful if you can't determine your relative position at any given time. A question years and miles ago from a fellow Finnish competitor, when his electronic navigation failed during our singlehanded around the world race, put the question to me this way: "how do you know where you are if you don't know where you are?" My dilemma, if I help him he will probably beat me, if not he might never make it to the finish line . . . no real dilemma. He made it to the finish line ahead of me.

According to people who keep track of things like this the Greeks understood the straight forward Polaris - Latitude connection in 300 B.C and used it for navigation but Longitude proved to be a much more complicated process requiring an accurate measurement of time. A pendulum clock on a moving ship wasn’t a reliable source for anything but frustration and shipwrecks, so the British Admiralty incentivized the search for a solution to the clock/time problem . And then along came a Yorkshire carpenter turned clockmaker named John Harrison. You will have to read Sobel's book for the rest of that fascinating story. With the earth now divided into described and published grids of longitude and latitude and the advent of a reliable time measurement machine seafaring folks could figure out where they were almost anywhere on the globe. Then came the task of charting oceans, land masses and obstructions - something that is still happening today.

It is worth noting here that not all the exploring seafaring folks on the planet at this time were dependent on clocks, longitude or latitude in order to make safe, reliable and repeatable voyages across oceans into unknown territories. Between 1405 -1433, China's Zheng He controlled a fleet of 317 large ships and over 28,000 sailors explored and mapped areas of Thailand, Asia, India and Africa using magnetic compasses, stars and astronomical observations while estimating speed and time by methods still used today. It was an extraordinary achievement, hard for me to comprehend the magnitude of effort and skill required to accomplish such exploration at that time.

We're sitting in a small semi-sheltered arctic bay discovered and named (False Strait!) by someone else (probably early 1700s), securely anchored between two nearly vertical rocky ridges, created by something else (millions of years ago) rising hundreds of feet above of our mast We chose this bay for a couple of reasons, proximity to Bellot Strait - our exit route from the Northwest Passage, and weather. Predictions for last night, today and tomorrow suggested we should find a place to hide for at least 36 hours. Force 6/7/8 winds (25 - 46kts), easterly, veering northerly for 24/36 hours meant finding a place with good anchor holding, sheltered from east, northeast and north winds if we wanted to relax and enjoy the experience. Did I mention snow? Everything visible this morning was covered with snow. Ice on our rigging, sails, decks and windows with wind noise at a pleasant but steady level makes us feel pretty thankful for our comfortable and heated little capsule.

All of this weather and scenery (except for the mountains and water) made me feel like I was waking up to a typical winter farm day in Nebraska - so I made breakfast pancakes for everyone. Given the Canadian influence on board Oo my Nebraska cakes turned into Canadian pancakes. Apparently food nationality changes when syrup is replaced by powdered sugar and lemon juice is added before the whole thing is neatly rolled and eaten. Spam as a side appears to be international - fried and flat, a poor substitute for bacon but we are in the Arctic, very close to where Franklin and his men still reside, and we are not having to eat our shoe leather to survive.

Fifteen years ago we piloted Ocean Watch through Bellot Strait after weaving our way through ice, wind and freezing water from Cambridge Bay to the western entrance of Bellot. That route took us to the south end of King William Island and the community of Gjoa Haven, the wintering base for Roald Amundsen during the first successful transit of the Northwest Passage (1903-1907). It is also very close to the place where the Franklin ships and crew were lost to the ice. We chose that route in 2009 because the west side of King William was completely blocked by ice. Our intention this time was to follow our 2009 route. However, a more direct route via Victoria Strait became ice free just a week ago and was completely open all the way to Bellot, saving many miles/hours to Bellot Strait.

I wanted to go to Gjoa Haven so the rest of the crew could experience a bit of what Amundsen and his crew experienced. Amundsen's achievement was truly remarkable - small ship, small crew and all willing to learn the ways of the Innuit to survive in an incredibly harsh environment. The Norwegian's welcomed and learned from the natives. According to the accounts from historians, the British not so much. To stand on the ground where Amundsen and his men lived, worked and explored for almost three years and to appreciate their efforts seemed like an experience one shouldn't miss. So, we stopped there again in spirit and hoisted a small ration of rum (very short supply) to their commitment and fortitude.