We departed Fort Ross, on the east side of Bellot Strait, early Tuesday morning, September 2. We’ve just passed our first official icebergs. Not floes or sheets like the ones we navigated earlier, but true icebergs. Sea ice forms when ocean water freezes into flat sheets that drift with wind and current. Icebergs, by contrast, are calved from glaciers—immense freshwater mountains, most of their mass hidden below the surface. I was at the helm when Mike pointed out what looked like an island emerging through low clouds. But it wasn’t on the charts. Through binoculars we realized it was ice—massive, like Waldron Island in the San Juans. And it wasn’t alone: a string of bergs drifted directly across our path north. The phrase “tip of the iceberg” has never felt so literal.

Once Mike took the helm, I bundled up and went out into the 27-degree air (not including windchill) to take photos and send them to Harry Stern, our polar ice scientist mentor at the University of Washington. Harry confirmed what we suspected: real icebergs, flowing south from the Humboldt and Petermann glaciers down Prince Regent Inlet. I hadn’t expected to see them so soon.

But that is the Northwest Passage - expect the unexpected with unknowns and surprises at every turn. After two challenging, unforgettable months, we are just days from exiting. The rewards have been immense: spectacular sights, generous people, unforgettable moments. But the Passage demanded everything of us— from unsurveyed charts, endless ice and fog, to winds that kept us on edge.

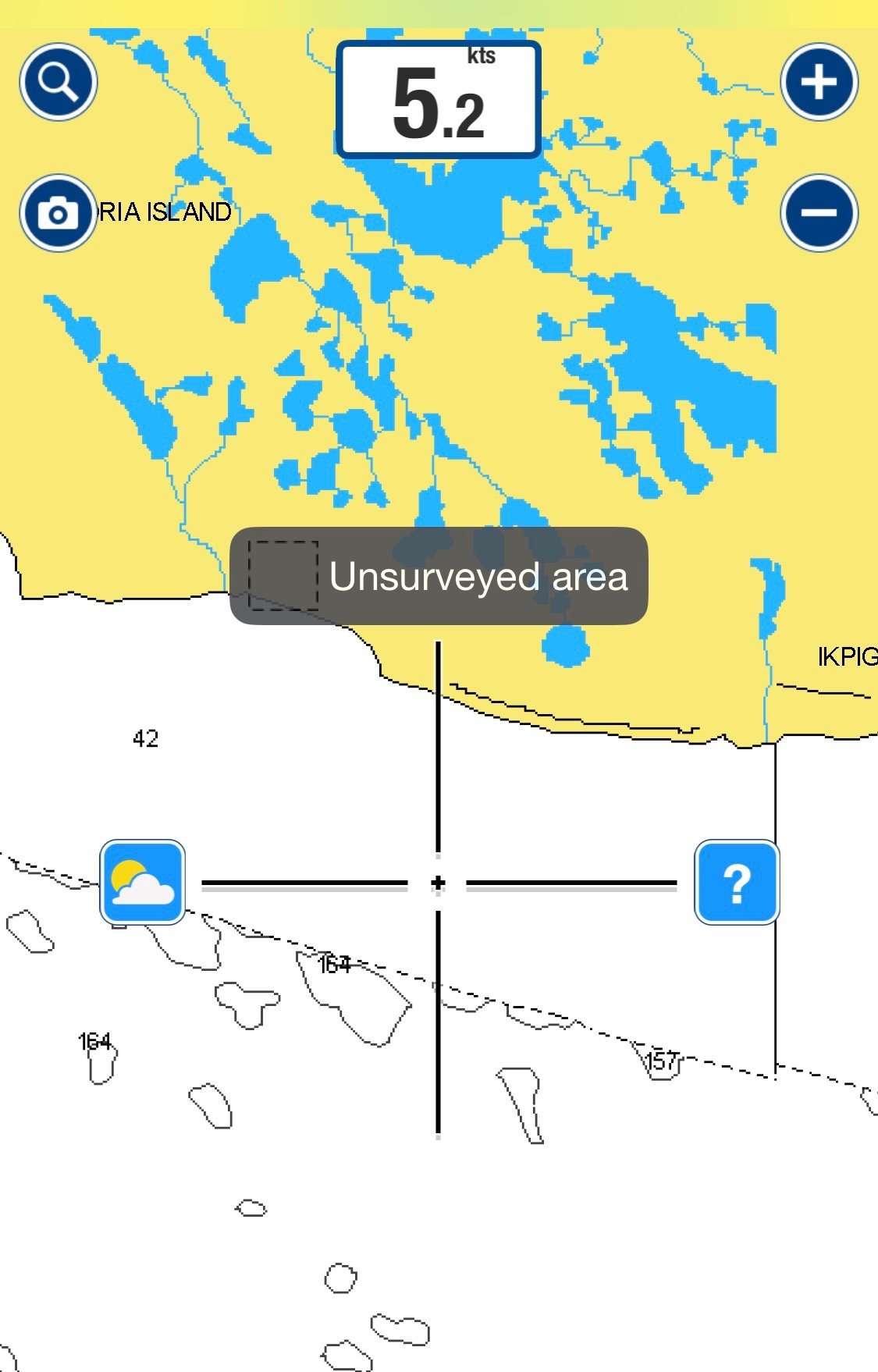

The navigation charts proved unreliable. More than once, we had to shut them off and feel our way through shifting, foggy channels. In Snow Goose Passage, our charts led us straight toward land. With shallows closing fast, we killed the chart and nosed along until deeper water appeared. Another time, leaving Cambridge Bay, the depth sounder dropped quickly from 50 feet to, to eight feet, to four… then to negative one. Crunch. We hit bottom. The boat stuck for several minutes as waves hit us broadside. Everyone snapped into emergency mode—life jackets, damage checks, bow thruster, engine revved hard. We finally worked free, shaken but intact. I was more than happy to leave those uncharted waters behind.

And then there were the windstorms. Week after week, systems brought 50+ knots sweeping from Alaska toward Cambridge Bay. With less sea ice to cause some friction and dampen the waves, storms struck harder. Friends on another boat even broke anchor one night when they recorded winds up to 55+ kts. A stark reminder of how vigilant we had to be.

We continuously recorded water and air temperatures. In McKinley Bay we recorded water temperatures in the 50s—warm enough for Mike and Tess to swim. These were some stark and vast differences from the first Around the Americas Expedition in 2009-10 that Mark and Dave pointed out. They recorded water temperatures around 34 degrees for the most part and they experienced very little wind.

The Passage is legendary for claiming lives. Mark and Mike devoured books about explorers, wrecks, and disasters; I chose not to, at least not while we were still in it. There were nights I wondered if we would get through. At Summers Harbour we waited for what felt like an eternity, steel boats coming and going as we stood watch, fending off ice chunks in the night. When we finally set out, the ice floes were thick, and I worried we’d left too soon. But we pushed on and made it through just in time—soon after, ice closed again between the Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf, making it very challenging for other vessels heading west.

We were also surprised by the sheer traffic—especially cruise ships. Small Arctic towns aren’t prepared for vast amounts of visitors, let alone luxury liners. No garbage facilities, no propane, limited provisions and astronomical prices. Many communities themselves struggled to receive supplies, with ice-choked passages holding back tugs and barges that brought in their diesel to warm their houses. Locals voiced their concerns about the lack of supplies, not out of unfriendliness, but for survival.

And the people—what can I say? Everywhere we stopped, we were welcomed as soon as we stepped foot on land or even as we anchored. We would have boats coming over to visit and greet us. In Tuktoyaktuk we were invited to watch some local hunters carve their fresh catch of Beluga Whale. I thought this would be difficult to watch, but they explained that this is sustenance for their long winters, the whale is rich in omega-3.

Summer is their time to stockpile—hunting caribou, reindeer, Arctic Char and beluga.

Click here for a fishing video.

With melting ice their nomadic traditions have shifted into fragile settlements. Now those infrastructures are crumbling under erosion and permafrost melt.

Seawalls have been built to fend off the waters—a temporary stopgap at best.

Climate change threaded through every conversation: unsafe hunting routes, food insecurity, and eroding communities on the brink of relocation. These towns are on the frontlines of climate change, warming four times faster than the global average. Their way of life, and the culture bound to it, is vanishing with the land itself. More than anything, these conversations will stay with me.

And then there are the politics of the Passage. We saw glimpses this summer—Chinese “research” vessels off Utqiagvik, Russian and Chinese ships testing Arctic trade routes. A reminder that as the ice retreats, the competition for control only grows.

Crossing the Northwest Passage was a feat—but more than that, it was a purpose. We saw climate change firsthand and listened to the voices of those living with the consequences. I have so much more to say, but that will be for another day. I believe in our mission of highlighting and bringing attention to these fragile coastal communities - we are one island sharing one ocean.

Over and Out -

Jenn