Beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas), often called “sea canaries” for their rich vocalizations, are among the most iconic marine mammals of the Arctic. Intelligent, social, and uniquely adapted to extreme environments, they offer an important lens into the rapidly changing northern ecosystem.

Belugas are small-to-medium-sized toothed whales in the same family as narwhals. Their range spans the Arctic Ocean and adjacent seas, from Hudson Bay and the Beaufort and Chukchi seas to the coastal waters of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Russia. Some populations migrate with the shifting sea ice, while others remain in specific estuaries and fjords year-round.

These whales typically live between 35 and 50 years, though some can reach 70. Calves are born in early summer after a gestation period of about 14 months. Newborns are gray, relying on their mothers for up to two years. Sexual maturity occurs between 8 and 15 years of age, depending on sex and population.

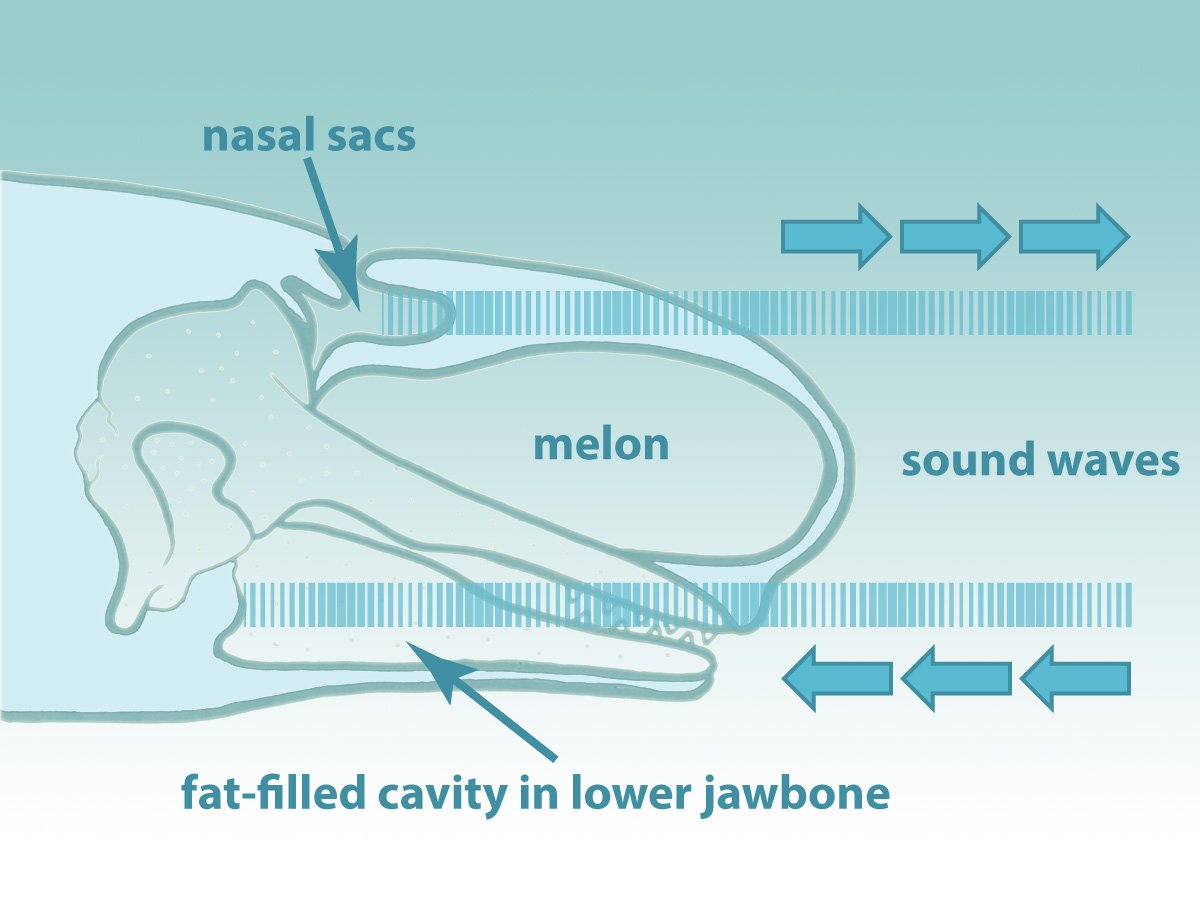

Built for life in the Arctic, adult belugas grow 13 to 20 feet long and weigh between 1,300 and 4,200 pounds. Their white coloration offers camouflage against sea ice, and their lack of a dorsal fin minimizes heat loss and allows them to swim easily beneath ice sheets. Belugas use echolocation to navigate, hunt, and communicate in the often dark and murky waters of the Arctic. They produce a series of high-frequency clicks and listen for the echoes that bounce back from objects around them. This allows them to "see" with sound, detecting the size, shape, distance, and even texture of prey or obstacles. Their bulbous forehead, called a melon, helps focus and direct sound waves, allowing them to echolocate effectively even under thick ice or in low-visibility conditions. Their thick blubber, which can measure up to six inches, provides insulation and stores energy for migrations or periods of food scarcity.

Belugas are opportunistic feeders with seasonal diets. They consume a wide variety of prey, including Arctic cod, capelin, herring, salmon, squid, shrimp, and benthic invertebrates such as crabs and marine worms. Using echolocation, they can hunt even in low-visibility conditions and often forage near the seafloor. In summer, belugas move into estuaries and river mouths, where prey is abundant and the shallows offer critical calving and molting grounds. Here, they are often seen rubbing against rocks to help slough off old skin.

Social by nature, belugas travel in small pods and display cooperative behaviors such as group hunting and shared calf care. Their communication repertoire, chirps, clicks, whistles, and squeals, is highly complex, used for both social bonding and navigation. Some studies suggest belugas use regional dialects and can recognize individual voices.

These whales also hold deep cultural and spiritual significance for Indigenous communities throughout the Arctic. For generations, groups such as the Inuit, Chukchi, Inuvialuit, and Iñupiat have relied on belugas for food, oil, and materials used in tools, clothing, and construction. Muktuk, made from beluga skin and blubber, is rich in vitamin C and remains a vital part of traditional diets. Hunts are guided by deep respect and traditional knowledge passed down through generations, forming the backbone of cultural continuity and food sovereignty.

Currently, we are in Utqiaġvik, Alaska, awaiting sea ice melt before continuing east along the Arctic coast. We hope to encounter belugas in their natural environment and observe their behaviors firsthand. Being here has reinforced how deeply intertwined these animals are with both Arctic ecosystems and the communities that depend on them.

In Utqiaġvik, beluga hunting continues to play a central role in Iñupiat life. Each spring and fall, hunters follow the migration routes of belugas through coastal waters and sea ice openings. These hunts, carried out in small boats or directly from the ice, demand an expert understanding of weather, ice, and whale behavior. More than a source of nutrition, the hunt strengthens community ties and cultural identity in an increasingly uncertain environment.

Historically, commercial whaling in the 18th and 19th centuries had a devastating impact on some beluga populations, especially in the St. Lawrence River. Today, non-Indigenous hunting is either banned or heavily regulated. In contrast, Indigenous harvests are managed through co-management systems that uphold both cultural traditions and conservation goals.

Ecologically, belugas are mid-level predators that reflect the health of the broader marine ecosystem. This makes them important indicator species. But despite their adaptability, they face mounting threats.

Climate change is transforming the Arctic. As sea ice diminishes, belugas must adapt to altered migration routes and increasing encounters with predators such as killer whales, which are expanding northward. Changing prey dynamics further complicate beluga survival. As Arctic waters warm and sea ice declines, belugas are losing access to their preferred prey, Arctic cod, which are rich in fat and thrive in cold water. They’re being replaced by saffron cod, which can survive in warmer conditions but offer less energy. This means belugas must eat much more to get the same nutrition, making survival harder.

Industrial pressures, including shipping and oil and gas development, bring underwater noise that disrupts echolocation and social communication. Pollutants such as mercury and PCBs accumulate in their blubber and can impair reproductive and immune health. Entanglement in fishing gear, while less common, poses an additional risk in regions with rising human activity. Some populations are already in trouble. The Cook Inlet belugas in Alaska, for example, are critically endangered. With fewer than 300 individuals remaining and no signs of recovery since being listed under the Endangered Species Act in 2008, they represent one of the most at-risk groups.

Globally, belugas are divided into more than 20 distinct stocks, with conservation statuses varying by region. While the IUCN lists the species as Least Concern overall, regional populations face different challenges. Some, like those in the Beaufort Sea and Hudson Bay, appear relatively stable. Others, especially in parts of the Russian Arctic, remain poorly studied due to limited access and data. Ongoing monitoring, habitat protection, and international cooperation are critical to ensuring their future.

Protecting belugas requires collaboration across borders. Arctic marine ecosystems transcend national boundaries, and conservation strategies must unite science, Indigenous knowledge, and policy. Key priorities include safeguarding estuaries and migration corridors, reducing vessel noise, limiting industrial disturbance, and supporting local monitoring programs. Tools such as satellite tracking, passive acoustics, and aerial surveys, when paired with traditional ecological knowledge, offer a clearer picture of how belugas respond to environmental change.

Belugas are more than charismatic symbols of the Arctic. They are vital to the ecological balance of northern waters and the cultural identity of the people who have stewarded these regions for generations. Their future depends on informed science, effective policy, and a commitment to honoring Indigenous leadership. In protecting belugas, we are also protecting the heart of the Arctic itself.

From the Field,

Grace Dalton