It was the night of our equator ceremony when I thought, for certain, we were being taken over by pirates. My heart leaped into my throat as I remembered Mark’s words… never ever let anyone board this vessel. When a boat rapidly approached One Ocean at night—men yelling and pointing a green laser beam that blinded our vision—I had the worst possible feeling of trouble.

The day had started as an epic morning, full of sunshine and good sailing in about twelve knots of breeze. The ocean was rich and vibrant with life—leaping dolphins, boobies feeding, and pilot whales by the dozens.

Jon, Tess and I were initiated, by King Neptune (Mark) from Pollywog status to Shellbacks at our equator crossing ceremony! Everything felt like a sailor’s fairytale come true.

(To watch the actual ceremony, you can find it on our YouTube channel - Oneislandoneocean)

But alas, one thing is certain with sailing: never grow too comfortable—everything changes.

It had been a busy day. We’d recorded a new podcast with our landlubbing crew members, Mike and Grace. By the time I served dinner—Mark’s leftover lentil soup—it was late. Around 7:30, we ate in the cockpit while watching the sunset, sailing steadily with the jib out, mizzen up, and a reef in the main. After dinner, Mark and Tess turned in to rest before their late-night watch while Jon stayed on deck.

I came up to take over when Jon mentioned there were a lot of lights on the water. I looked out and saw hundreds of small white lights glowing in the darkness. As his words hung in the air, a green laser beam suddenly flashed on from the port side. It stayed on us, blinding me, as it moved closer.

I jumped behind the wheel and yelled for Jon to take us off autopilot. I could make out a small wooden fishing boat heading straight toward us. Within feet now, men were shouting in the dark, holding the laser so we couldn’t see who—or what—they were. I yelled for everyone on deck. Mark and Tess were there instantly.

Still visually impaired by the laser, with a fishing boat on our port side and One Ocean under full sail, I tried to steady the helm. My mind raced, but one thing became clear: if they meant harm, it would have already happened. They were trying to warn us.

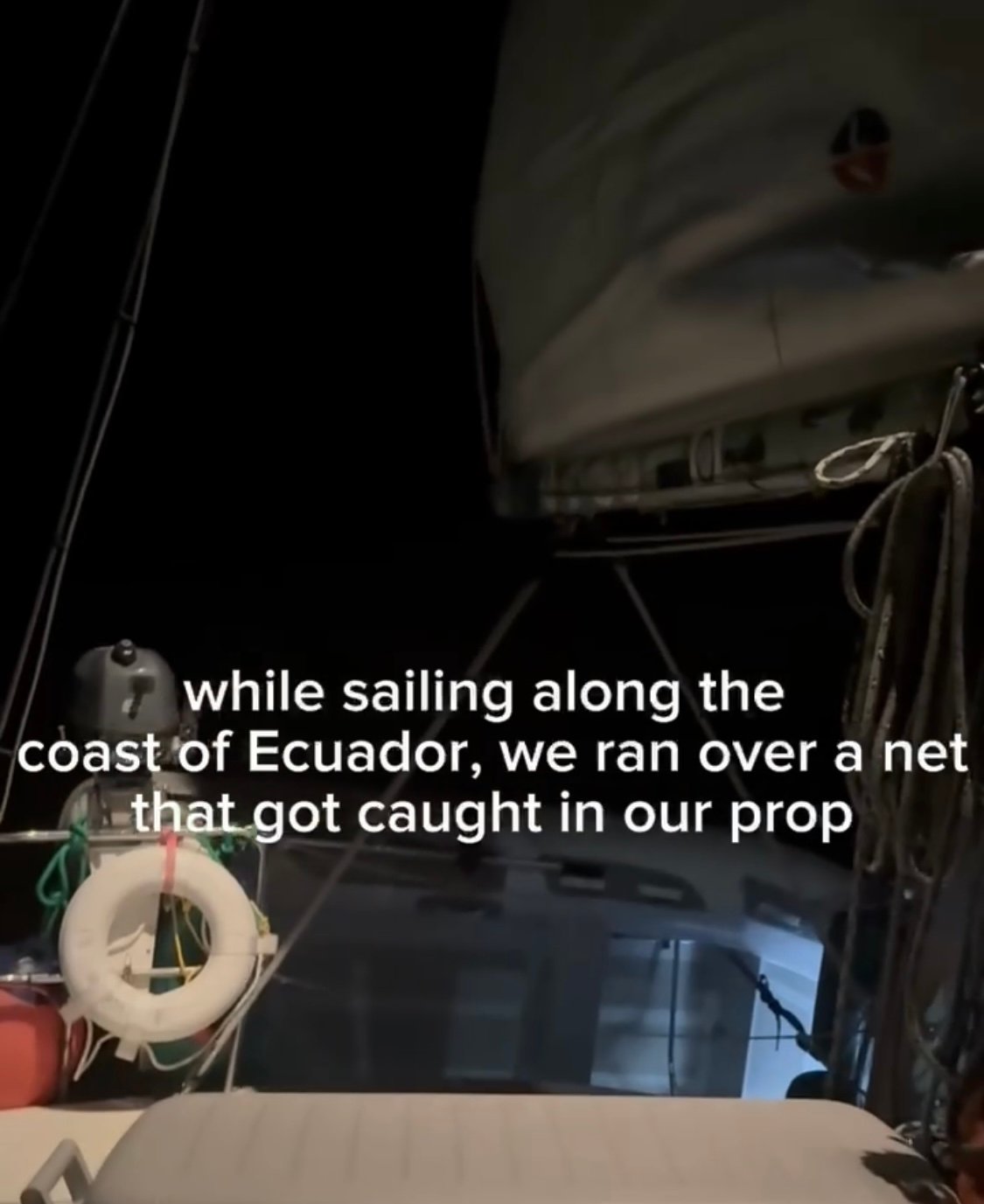

We turned on the spreader lights and a spotlight and saw the problem—we’d run over a longline net. A squid net. Jon jumped onto the swim step and cut it free while the fishermen continued yelling beside us.

It wasn’t just a few boats out fishing. There were hundreds.

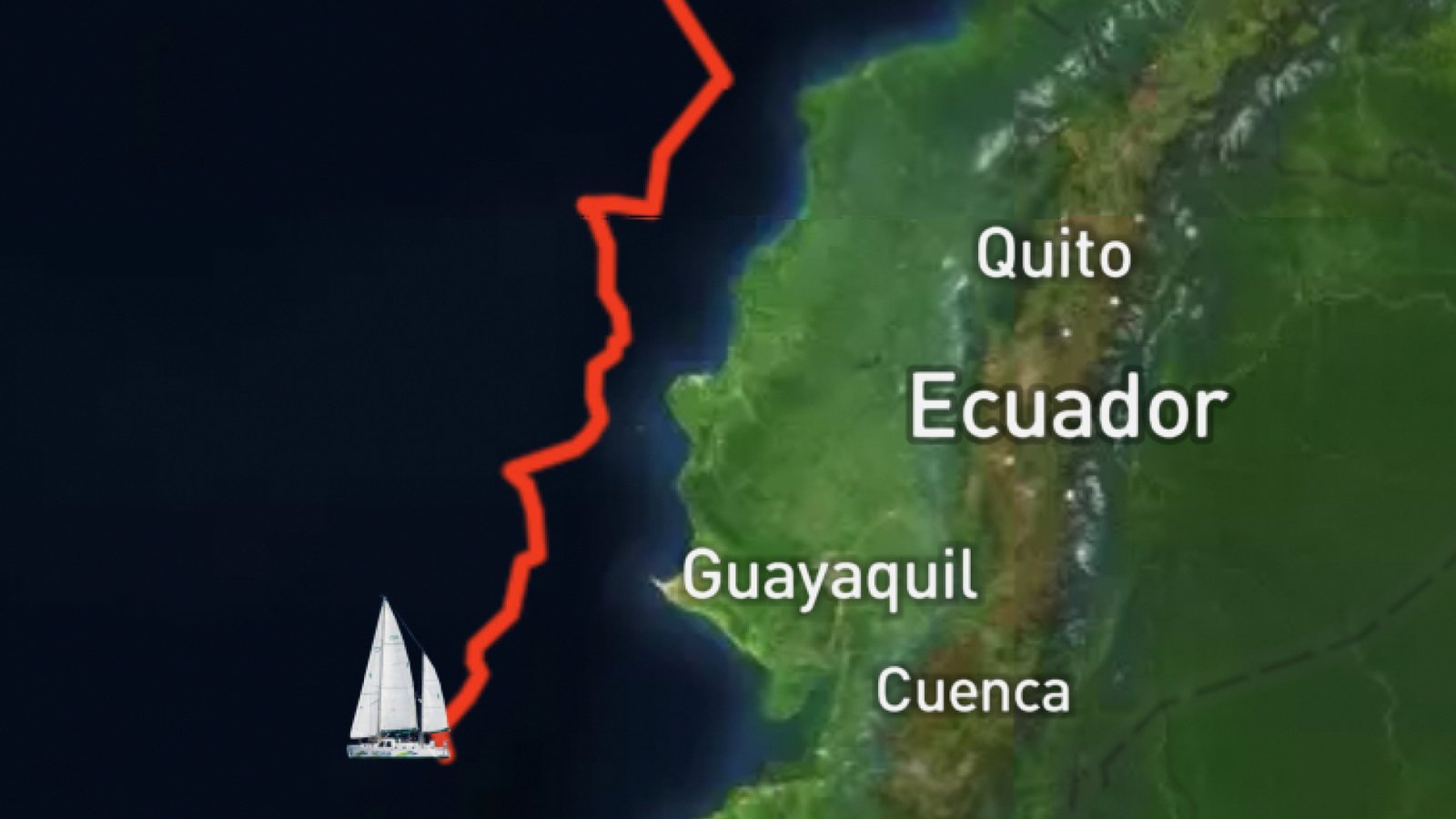

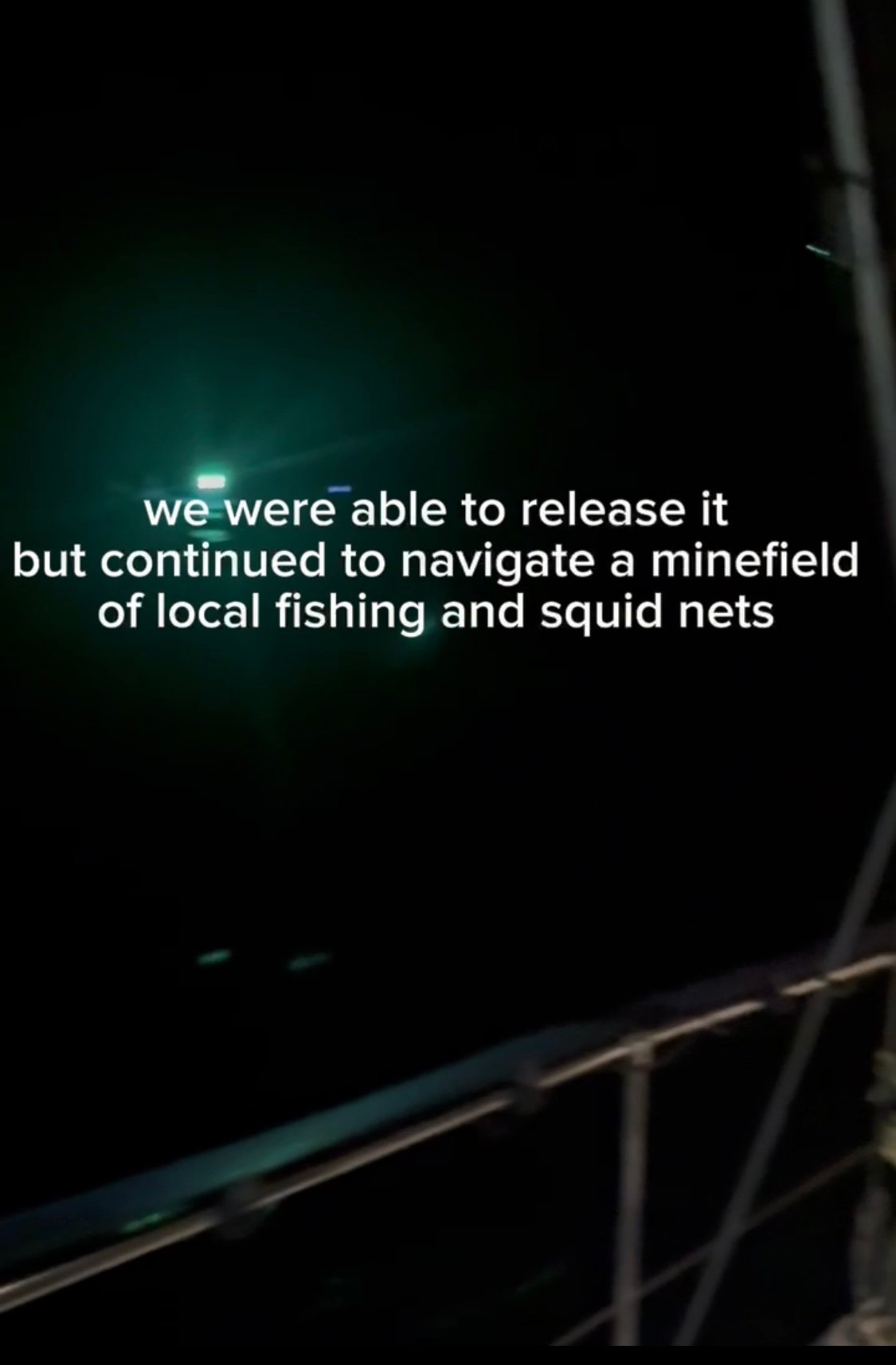

Not far beyond that, we ran into another cluster of vessels—white, red, and green laser lights darting around us. We furled in the jib and started the engine. The radar was useless; these small boats didn’t show up, and they were all connected by netting. It was a dark maze, and it felt utterly impossible to navigate.

While Tess googled the meaning of the lights, we slowly wove from port to starboard, scanning the water. We learned the green lasers were used to attract squid. This type of fishing is common along parts of the equatorial Pacific, where fleets of small vessels work together at night, stringing long nets between boats. The green lights attract squid to the surface, but for transiting vessels it creates an invisible hazard—nets are nearly impossible to see, rarely marked clearly, and often extend far beyond the boats themselves. All this for f#$% calamari.

The chaos was overwhelming—lasers flashing, spotlights glaring, men yelling, boats racing toward us in the dark. The stress reminded me of weaving through ice, something we never did at night—and ice doesn’t yell at you in another language. My shoulders crept higher and tighter with every net we drifted over.

Our only option was to head west toward a military exclusion zone. Risky, but fishermen likely wouldn’t set nets there. As we moved offshore, the congestion thinned. Still, boats continued to intercept us, lighting us up and shouting warnings. One guided us for miles, leading us past their netting.

Another net slid beneath the boat, glowing with phosphorescence. I threw the engine into neutral. Somehow, we slipped through untouched.

After six hours of this, my shoulders aching from tension, I collapsed into bed. We were finally far enough offshore, near the military boundary, with fewer fishermen—but vigilance remained essential.

Ecuador was a place I’d always wanted to visit. After that night, I couldn’t wait to get away. And while calamari is still one of my favorites, I’ll never look at it the same again.